With KOSA passed, the information i can access as a minor will be limited and censored, under the guise of “protecting me”, which is the responsibility of my parents, NOT the government. I have learned so much about the world and about myself through social media, and without the diverse world i have seen, i would be a completely different, and much worse, person. For a country that prides itself in the free speech and freedom of its peoples, this bill goes against everything we stand for! – Alan, 15

___________________

If information is put through a filter, that’s bad. Any and all points of view should be accessible, even if harmful so everyone can get an understanding of all situations. Not to mention, as a young neurodivergent and queer person, I’m sure the information I’d be able to acquire and use to help myself would be severely impacted. I want to be free like anyone else. – Sunny, 15

___________________

How young people feel about the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) matters. It will primarily affect them, and many, many teenagers oppose the bill. Some have been calling and emailing legislators to tell them how they feel. Others have been posting their concerns about the bill on social media. These teenagers have been baring their souls to explain how important social media access is to them, but lawmakers and civil liberties advocates, including us, have mostly been the ones talking about the bill and about what’s best for kids, and often we’re not hearing from minors in these debates at all. We should be — these young voices should be essential when talking about KOSA.

So, a few weeks ago, we asked some of the young advocates fighting to stop the Kids Online Safety Act a few questions:

– How has access to social media improved your life? What do you gain from it?

– What would you lose if KOSA passed? How would your life be different if it was already law?

Within a week we received over 3,000 responses. As of today, we have received over 5,000.

These answers are critical for legislators to hear. Below, you can read some of these comments, sorted into the following themes (though they often overlap):

These comments show that thoughtful young people are deeply concerned about the proposed law’s fallout, and that many who would be affected think it will harm them, not help them. Over 700 of those who responded reported that they were currently sixteen or under—the age under which KOSA’s liability is applicable. The average age of those who answered the survey was 20 (of those who gave their age—the question was optional, and about 60% of people responded). In addition to these two questions, we also asked those taking the survey if they were comfortable sharing their email address for any journalist who might want to speak with them; unfortunately much coverage usually only mentions one or two of the young people who would be most affected. So, journalists: We have contact info for over 300 young people who would be happy to speak to you about why social media matters to them, and why they oppose KOSA.

Individually, these answers show that social media, despite its current problems, offer an overall positive experience for many, many young people. It helps people living in remote areas find connection; it helps those in abusive situations find solace and escape; it offers education in history, art, health, and world events for those who wouldn’t otherwise have it; it helps people learn about themselves and the world around them. (Research also suggests that social media is more helpful than harmful for young people.)

And as a whole, these answers tell a story that is 180° different from that which is regularly told by politicians and the media. In those stories, it is accepted as fact that the majority of young people’s experiences on social media platforms are harmful. But from these responses, it is clear that many, many young people also experience help, education, friendship, and a sense of belonging there—precisely because social media allows them to explore, something KOSA is likely to hinder. These kids are deeply engaged in the world around them through these platforms, and genuinely concerned that a law like KOSA could take that away from them and from other young people.

Here are just a few of the thousands of reasons they’re worried.

Note: We are sharing individuals’ opinions, without editing. We do not necessarily endorse them or their interpretation of KOSA.

KOSA Will Harm Rights That Young People Know They Ought to Have

One of the most important things that would be lost is the freedom of speech – a given right that is crucial to a healthy, functioning environment. Not every speech is morally okay, but regulating what speech is deemed “acceptable” constricts people’s rights; a clear violation of the First Amendment. Those who need or want to access certain information are not allowed to – not because the information will harm them or others, but for the reason that a certain portion of people disagree with the information. If the country only ran on what select people believed, we would be a bland, monotonous place. This country thrives on diversity, whether it be race, gender, sex, or any other personal belief. If KOSA was passed, I would lose my safe spaces, places where I can go to for mental health, places that make me feel more like a human than just some girl. No more would I be able to fight for ideas and beliefs I hold, nor enjoy my time on the internet either. – Anonymous, 16

___________________

I, and many of my friends, grew up in an Internet where remaining anonymous was common sense, and where revealing your identity was foolish and dangerous, something only to be done sparingly, with a trusted ally at your side, meeting at a common, crowded public space like a convention or a college cafeteria. This bill spits in the face of these very practical instincts, forces you to dox yourself, and if you don’t want to be outed, you must be forced to withdraw from your communities. From your friends and allies. From the space you have made for yourself, somewhere you can truly be yourself with little judgment, where you can find out who you really are, alongside people who might be wildly different from you in some ways, and exactly like you in others. I am fortunate to have parents who are kind and accepting of who I am. I know many people are nowhere near as lucky as me. – Maeve, 25

___________________

I couldn’t do activism through social media and I couldn’t connect with other queer individuals due to censorship and that would lead to loneliness, depression other mental health issues, and even suicide for some individuals such as myself. For some of us the internet is the only way to the world outside of our hateful environments, our only hope. Representation matters, and by KOSA passing queer children would see less of age appropriate representation and they would feel more alone. Not to mention that KOSA passing would lead to people being uninformed about things and it would start an era of censorship on the internet and by looking at the past censorship is never good, its a gateway to genocide and a way for the government to control. – Sage, 15

___________________

Privacy, censorship, and freedom of speech are not just theoretical concepts to young people. Their rights are often already restricted, and they see the internet as a place where they can begin to learn about, understand, and exercise those freedoms. They know why censorship is dangerous; they understand why forcing people to identify themselves online is dangerous; they know the value of free speech and privacy, and they know what they’ve gained from an internet that doesn’t have guardrails put up by various government censors.

KOSA Could Impact Young People’s Artistic Education and Opportunities

I found so many friends and new interests from social media. Inspirations for my art I find online, like others who have an art style I admire, or models who do poses I want to draw. I can connect with my friends, send them funny videos and pictures. I use social media to keep up with my favorite YouTubers, content creators, shows, books. When my dad gets drunk and hard to be around or my parents are arguing, I can go on YouTube or Instagram and watch something funny to laugh instead. It gives me a lot of comfort, being able to distract myself from my sometimes upsetting home life. I get to see what life is like for the billions of other people on this planet, in different cities, states, countries. I get to share my life with my friends too, freely speaking my thoughts, sharing pictures, videos, etc.

I have found my favorite YouTubers from other social media platforms like tiktok, this happened maybe about a year ago, and since then I think this is the happiest I have been in a while. Since joining social media I have become a much more open minded person, it made me interested in what others lives are like. It also brought awareness and educated me about others who are suffering in the world like hunger, poor quality of life, etc. Posting on social media also made me more confident in my art, in the past year my drawing skills have immensely improved and I’m shocked at myself. Because I wanted to make better fan art, inspire others, and make them happy with my art. I have been introduce to many styles of clothing that have helped develop my own fun clothing style. It powers my dreams and makes me want to try hard when I see videos shared by people who have worked hard and made it. – Anonymous, 15

___________________

As a kid I was able to interact in queer and disabled and fandom spaces, so even as a disabled introverted child who wasn’t popular with my peers I still didn’t feel lonely. The internet is arguably a safer way to interact with other fans of media than going to cons with strangers, as long as internet safety is really taught to kids. I also get inspiration for my art and writing from things I’ve only discovered online, and as an artist I can’t make money without the internet and even minors do commissions. The issue isn’t that the internet is unsafe, it’s that internet safety isn’t taught anymore. – Rachel, 19

___________________

i am an artist, and sharing my things online makes me feel happy and good about myself. i love seeing other people online and knowing that they like what i make. when i make art, im always nervous to show other people. but when i post it online i feel like im a part of something, and that im in a community where i feel that i belong. – Anonymous, 15

___________________

Social media has saved my life, just like it has for many young people. I have found safe spaces and motivation because of social media, and I have never encountered anything negative or harmful to me. With social media I have been able to share my creativity (writing, art, and music) and thoughts safely without feeling like I’m being held back or oppressed. My creations have been able to inspire and reach so many people, just like how other people’s work have reached me. Recently, I have also been able to help the library I volunteer at through the help of social media.

What I do in life and all my future plans (career, school, volunteer projects, etc.) surrounds social media, and without it I wouldn’t be able to share what I do and learn more to improve my works and life. I wouldn’t be able to connect with wonderful artists, musicians, and writers like I do now. I would be lost and feel like I don’t have a reason to do what I do. If KOSA is passed, I wouldn’t be able to get the help I need in order to survive. I’ve made so many friends who have been saved because of social media, and if this bill gets passed they will also be affected. Guess what? They wouldn’t be able to get the help they need either.

If KOSA was already a law when I was just a bit younger, I wouldn’t even be alive. I wouldn’t have been able to reach help when I needed it. I wouldn’t have been able to share my mind with the world. Social media was the reason I was able to receive help when I was undergoing abuse and almost died. If KOSA was already a law, I would’ve taken my life, or my abuser would have done it before I could. If KOSA becomes a law now, I’m certain that the likeliness of that happening to kids of any age will increase. – Anonymous, 15

___________________

A huge number of young artists say they use social media to improve their skills, and in many cases, the avenue by which they discovered their interest in a type of art or music. Young people are rightfully worried that the magic moment where you first stumble upon an artist or a style that changes your entire life will be less and less common for future generations if KOSA passes. We agree: KOSA would likely lead platforms to limit that opportunity for young people to experience unexpected things, forcing their online experiences into a much smaller box under the guise of protecting them.

Also, a lot of young people told us they wanted to, or were developing, an online business—often an art business. Under KOSA, young people could have less opportunities in the online communities where artists share their work and build a customer base, and a harder time navigating the various communities where they can share their art.

KOSA Will Hurt Young People’s Ability to Find Community Online

Social media has allowed me to connect with some of my closest friends ever, probably deeper than some people in real life. i get to talk about anything i want unimpeded and people accept me for who i am. in my deepest and darkest moments, knowing that i had somewhere to go was truly more relieving than anything else. i’ve never had the courage to commit suicide, but still, if it weren’t for social media, i probably wouldn’t be here, mentally & emotionally at least.

i’d lose the space that accepts me. i’d lose the only place where i can be me. in life, i put up a mask to appease my parents and in some cases, my friends. with how extreme the u.s. is becoming these days, i could even lose my life. i would live my days in fear. i’m terrified of how fast this country is changing and if this bill passes, saying i would fall into despair would be an understatement. people say to “be yourself”, but they don’t understand that if i were to be my true self tomorrow, i could be killed. – march, 14

___________________

Without the internet, and especially the rhythm gaming community which I found through Discord, I would’ve most likely killed myself at 13. My time on here has not been perfect, as has anyone’s but without the internet I wouldn’t have been the person I am today. I wouldn’t have gotten help recognizing that what my biological parents were doing to me was abuse, the support I’ve received for my identity (as queer youth) and the way I view things, with ways to help people all around the world and be a more mindful ally, activist, and thinker, and I wouldn’t have met my mom.

I love my chosen mom. We met at a Dance Dance Revolution tournament in April of last year and have been friends ever since. When I told her that she was the first person I saw as a mother figure in my life back in November, I was bawling my eyes out. I’m her mije, and she’s my mom. love her so much that saying that doesn’t even begin to express exactly how much I love her.

I love all my chosen family from the rhythm gaming community, my older sisters and siblings, I love them all. I have a few, some I talk with more regularly than others. Even if they and I may not talk as much as we used to, I still love them. They mean so much to me. – X86, 15

___________________

i spent my time in public school from ages 9-13 getting physically and emotionally abused by special ed aides, i remember a few months after i left public school for good, i saw a post online that made me realize that what i went through wasn’t normal. if it wasn’t for the internet, i wouldn’t have come to terms with my autism, i would have still hated myself due to not knowing that i was genderqueer, my mental health would be significantly worse, and i would probably still be self harming, which is something i stopped doing at 13. besides the trauma and mental health side of things, something important to know is that spaces for teenagers to hang out have been eradicated years ago, minors can’t go to malls unless they’re with their parents, anti loitering laws are everywhere, and schools aren’t exactly the best place for teenagers to hang out, especially considering queer teens who were murdered by bullies (such as brianna ghey or nex benedict), the internet has become the third space that teenagers have flocked to as a result. – Anonymous, 17

___________________

KOSA is anti-community. People online don’t only connect over shared interests in art and music—they also connect over the difficult parts of their lives. Over and over again, young people told us that one of the most valuable parts of social media was learning that they were not alone in their troubles. Finding others in similar circumstances gave them a community, as well as ideas to improve their situations, and even opportunities to escape dangerous situations.

KOSA will make this harder. As platforms limit the types of recommendations and public content they feel safe sharing with young people, those who would otherwise find communities or potential friends will not be as likely to do so. A number of young people explained that they simply would never have been able to overcome some of the worst parts of their lives alone, and they are concerned that KOSA’s passage would stop others from ever finding the help they did.

KOSA Could Seriously Hinder People’s Self-Discovery

I am a transgender person, and when I was a preteen, looking down the barrel of the gun of puberty, I was miserable. I didn’t know what was wrong I just knew I’d rather do anything else but go through puberty. The internet taught me what that was. They told me it was okay. There were things like haircuts and binders that I could use now and medical treatment I could use when I grew up to fix things. The internet was there for me too when I was questioning my sexuality and again when my mental health was crashing and even again when I was realizing I’m not neurotypical. The internet is a crucial source of information for preteens and beyond and you cannot take it away. You cannot take away their only realistically reachable source of information for what the close-minded or undereducated adults around them don’t know. – Jay, 17

___________________

Social media has improved my life so much and led to how I met my best friend, I’ve known them for 6+ years now and they mean so much to me. Access to social media really helps me connect with people similar to me and that make me feel like less of an outcast among my peers, being able to communicate with other neurodivergent queer kids who like similar interests to me. Social media makes me feel like I’m actually apart of a community that won’t judge me for who I am. I feel like I can actually be myself and find others like me without being harassed or bullied, I can share my art with others and find people like me in a way I can’t in other spaces. The internet & social media raised me when my parents were busy and unavailable and genuinely shaped the way I am today and the person I’ve become. – Anonymous, 14

___________________

The censorship likely to come from this bill would mean I would not see others who have similar struggles to me. The vagueness of KOSA allows for state attorney generals to decide what is and is not appropriate for children to see, a power that should never be placed in the hands of one person. If issues like LGBT rights and mental health were censored by KOSA, I would have never realized that I AM NOT ALONE. There are problems with children and the internet but KOSA is not the solution. I urge the senate to rethink this bill, and come up with solutions that actually protect children, not put them in more danger, and make them feel ever more alone. – Rae, 16

___________________

KOSA would effectively censor anything the government deems “harmful,” which could be anything from queerness and fandom spaces to anything else that deviates from “the norm.” People would lose support systems, education, and in some cases, any way to find out about who they are. I’ll stop beating around the bush, if it wasn’t for places online, I would never have discovered my own queerness. My parents and the small circle of adults I know would be my only connection to “grown-up” opinions, exposing me to a narrow range of beliefs I would likely be forced to adopt. Any kids in positions like mine would have no place to speak out or ask questions, and anything they bring up would put them at risk. Schools and families can only teach so much, and in this age of information, why can’t kids be trusted to learn things on their own? – Anonymous, 15

___________________

Social media helped me escape a very traumatic childhood and helped me connect with others. quite frankly, it saved me from being brainwashed. – Milo, 16

___________________

Social media introduced me to lifelong friends and communities of like-minded people; in an abusive home, online social media in the 2010s provided a haven of privacy, safety, and information. I honed my creativity, nurtured my interests and developed my identity through relating and talking to people to whom I would otherwise have been totally isolated from. Also, unrestricted internet access actually taught me how to spot shady websites and inappropriate content FAR more effectively than if censorship had been at play like it is today.

A couple of the friends I made online, as young as thirteen, were adults; and being friends with adults who knew I was a child, who practiced safe boundaries with me yet treated me with respect, helped me recognise unhealthy patterns in predatory adults. I have befriended mothers and fathers online through games and forums, and they were instrumental in preventing me being groomed by actual pedophiles. Had it not been for them, I would have wound up terribly abused by an “in real life” adult “friend”. Instead, I recognised the differences in how he was treating me (infantilising yet praising) vs how my adult friends had treated me (like a human being), and slowly tapered off the friendship and safely cut contact.

As I grew older, I found a wealth of resources on safe sex and sexual health education online. Again, if not for these discoveries, I would most certainly have wound up abused and/or pregnant as a teenager. I was never taught about consent, safe sex, menstruation, cervical health, breast health, my own anatomy, puberty, etc. as a child or teenager. What I found online– typically on Tumblr and written with an alarming degree of normalcy– helped me understand my body and my boundaries far more effectively than “the talk” or in-school sex ed ever did. I learned that the things that made me panic were actually normal; the ins and outs of puberty and development, and, crucially, that my comfort mattered most. I was comfortable and unashamed of being a virgin my entire teen years because I knew it was okay that I wasn’t ready. When I was ready, at twenty-one, I knew how to communicate with my partner and establish safe boundaries, and knew to check in and talk afterwards to make sure we both felt safe and happy. I knew there was no judgement for crying after sex and that it didn’t necessarily mean I wasn’t okay. I also knew about physical post-sex care; e.g. going to the bathroom and cleaning oneself safely.

AGAIN, I would NOT have known any of this if not for social media. AT ALL. And seeing these topics did NOT turn me into a dreaded teenage whore; if anything, they prevented it by teaching me safety and self-care.

I also found help with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders– learning to define them enabled me to seek help. I would not have had this without online spaces and social media. As aforementioned too, learning, sometimes through trial of fire, to safely navigate the web and differentiate between safe and unsafe sites was far more effective without censored content. Censorship only hurts children; it has never, ever helped them. How else was I to know what I was experiencing at home was wrong? To call it “abuse”? I never would have found that out. I also would never have discovered how to establish safe sexual AND social boundaries, or how to stand up for myself, or how to handle harassment, or how to discover my own interests and identity through media. The list goes on and on and on. – June, 21

___________________

One of the claims that KOSA’s proponents make is that it won’t stop young people from finding the things they already want to search for. But we read dozens and dozens of comments from people who didn’t know something about themselves until they heard others discussing it—a mental health diagnosis, their sexuality, that they were being abused, that they had an eating disorder, and much, much more.

Censorship that stops you from looking through a library is still dangerous even if it doesn’t stop you from checking out the books you already know. It’s still a problem to stop young people in particular from finding new things that they didn’t know they were looking for.

KOSA Could Stop Young People from Getting Accurate News and Valuable Information

Social media taught me to be curious. It taught me caution and trust and faith and that simply being me is enough. It brought me up where my parents failed, it allowed me to look into stories that assured me I am not alone where I am now. I would be fucking dead right now if it weren’t for the stories of my fellow transgender folk out there, assuring me that it gets better.

I’m young and I’m not smart but I know without social media, myself and plenty of the people I hold dear in person and online would not be alive. We wouldn’t have news of the atrocities happening overseas that the news doesn’t report on, we wouldn’t have mentors to help teach us where our parents failed. – Anonymous, 16

___________________

Through social media, I’ve learned about news and current events that weren’t taught at school or home, things like politics or controversial topics that taught me nuance and solidified my concept of ethics. I learned about my identity and found numerous communities filled with people I could socialize with and relate to. I could talk about my interests with people who loved them just as much as I did. I found out about numerous different perspectives and cultures and experienced art and film like I never had before. My empathy and media literacy greatly improved with experience. I was also able to gain skills in gathering information and proper defences against misinformation. More technically, I learned how to organize my computer and work with files, programs, applications, etc; I could find guides on how to pursue my hobbies and improve my skills (I’m a self-taught artist, and I learned almost everything I know from things like YouTube or Tumblr for free). – Anonymous, 15

___________________

A huge portion of my political identity has been shaped by news and information I could only find on social media because the mainstream news outlets wouldn’t cover it. (Climate Change, International Crisis, Corrupt Systems, etc.) KOSA seems to be intentionally working to stunt all of this. It’s horrifying. So much of modern life takes place on the internet, and to strip that away from kids is just another way to prevent them from formulating their own thoughts and ideas that the people in power are afraid of. Deeply sinister. I probably would have never learned about KOSA if it were in place! That’s terrifying! – Sarge, 17

___________________

I’ve met many of my friends from [social media] and it has improved my mental health by giving me resources. I used to have an eating disorder and didn’t even realize it until I saw others on social media talking about it in a nuanced way and from personal experience. – Anonymous, 15

___________________

Many young people told us that they’re worried KOSA will result in more biased news online, and a less diverse information ecosystem. This seems inevitable—we’ve written before that almost any content could fit into the categories that politicians believe will cause minors anxiety or depression, and so carrying that content could be legally dangerous for a platform. That could include truthful news about what’s going on in the world, including wars, gun violence, and climate change.

“Preventing and mitigating” depression and anxiety isn’t a goal of any other outlet, and it shouldn’t be required for social media platforms. People have a right to access information—both news and opinion— in an open and democratic society, and sometimes that information is depressing or anxiety-inducing. To truly “prevent and mitigate” self-destructive behaviors, we must look beyond the media to systems that allow all humans to have self-respect, a healthy environment, and healthy relationships—not hiding truthful information that is disappointing.

Young People’s Voices Matter

While KOSA’s sponsors intend to help these young people, those who responded to the survey don’t see it that way. You may have noticed that it’s impossible to limit these complex and detailed responses into single categories—many childhood abuse victims found help as well as arts education on social media; many children connected to communities that they otherwise couldn’t and learned something essential about themselves in doing so. Many understand that KOSA would endanger their privacy, and also know it could harm marginalized kids the most.

In reading thousands of these comments, it becomes clear that social media itself was not in itself a solution to the issues they experienced. What helped these young people was other people. Social media was where they were able to find and stay connected with those friends, communities, artists, activists, and educators. When you look at it this way, of course KOSA seems absurd: social media has become an essential element of young peoples’ lives, and they are scared to death that if the law passes, that part of their lives will disappear. Older teens and twenty-somethings, meanwhile, worry that if the law had been passed a decade ago, they never would have become the person that they did. And all of these fears are reasonable.

There were thousands more comments like those above. We hope this helps balance the conversation, because if young people’s voices are suppressed now—and if KOSA becomes law—it will be much more difficult for them to elevate their voices in the future.

Republished from the EFF’s Deep Links blog.

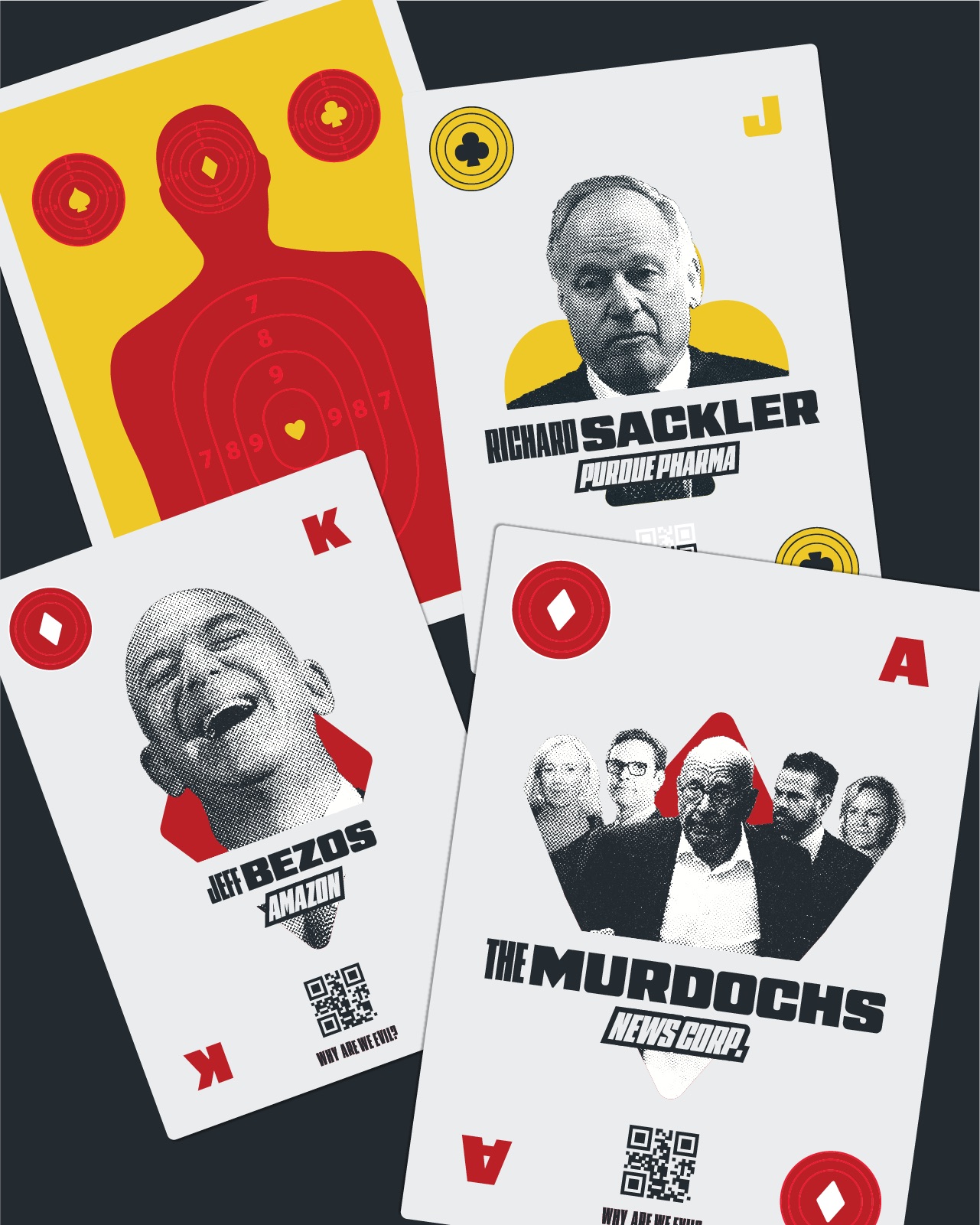

A design for the Most Wanted CEO playing cards

A design for the Most Wanted CEO playing cards

Re:

In the 2600 case (link above), the judge explicitly ruled that it doesn't matter how easy it is to circumvent. The exact words were that a technological measure can be effective "whether or not it is a strong means of protection."

So you are correct... if the judge follows precedent, he'll rule against such an argument.

Re: Re: GNU FDL vs CC-BY-SA

I think you're not seeing the root of the problem. The "non-commercial" nature of CC licenses is really nothing new - the GPL is often similarly confused by people who don't realize that it doesn't prevent commercial use. Although you have a point that the CC-NC licenses might be confusing the issue (guilt by association) enough other commerce-friendly licenses have had the same problem that I think the issue goes deeper than that.

I think you are fighting against a propaganda machine, in the form of media companies that purvey anything that's not "all right reserved" as "non-commercial". For decades, increasingly lop-sided copyright law and the propaganda surrounding it has persuaded people to believe that all free licenses are non-commercial.

I don't think that forking or creating your own license would do help - I think you'll end up fighting the exact same battle.

Look at it from their point of view...

The purpose of copyright law is to promote progress, right? Without absolute control over every conceivable image, how will religious groups be encouraged to build more mysterious stone monuments?

Think about it - the sphynx is 5000 years old, stonehenge is 4500 years old, and the moai statues of Easter Island are only 500 years old. While these once were obviously commonly built, there haven't been any mysterious stone monuments built in centuries! It's quite obvious that the lack of copyright is what's preventing more of these sort of things from being created - just like it's the lack of pirates that's causing global warming!

We must encourage groups like to EHO to make these claims - it's the only way to get people to contribute to our culture!

It's not only wrong, it's dangerous.

It's not only incorrect to treat copyright as property, it's downright dangerous. The absurdities we see everyday from copyright maximalists are an example of what happens when you think of copyright as a property right.

Sheldon Richman wrote a very compelling article about why this is. I strongly urge everybody to read it, as it succinctly illustrates the point. It's telling that a year after he wrote it, the article comments contain no further refutation from those who disagree with him than "nuh-uh!"

If??!?!

The record labels are *already* doing this, and have been for as long as I can remember.

http://boingboing.net/2009/12/07/major-record-labels.html

http://www.negativland.com/albini.html

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20090602/2308085105.shtml

The minister is correct with his outrage!

Where exactly are the fast cars!?!?!? Did the the app author forget about Ferrari and Lamborghini? (Not to mention Bugatti, which although technically German was founded by an Italian.)

It's an outrage I say!